This English translation of an article by Loïc Morel was published on sovrnbitcoiner.com website.

“He is too great,” they all said, and the rooster of India, who had come into the world with spurs and believed himself to be emperor, inflated himself like a building all sails out, and walked straight on him in great fury and red to the eyes. The poor duck did not know whether to stop or walk: he was saddened to be scorned by all the ducks of the court.

One of the most important scourges on the Bitcoin protocol is address reuse. The transparency and distribution of the network makes this practice dangerous for the user’s privacy. To avoid problems related to this, it is advisable to use a new blank receiving address for any new payment entering to a wallet, which can be complicated to achieve in some cases.

This compromise is as old as the White Paper. Satoshi already warned us against this risk in his book published at the end of 2008:

“as an additional firewall, a new key pair should be used for each transaction to keep them from being linked to a common owner”

Many solutions exist to receive multiple payments, without producing address reuse. Each of them has its own trade-offs and disadvantages. Among all these solutions, there is the BIP47, a proposal developed by Justus Ranvier and published in 2015 to generate reusable payment codes. Their goal is to be able to carry out several transactions to the same person, without reusing an address.

Initially, this proposal received a contemptuous reception from part of the community, and it was never added to Bitcoin Core. Some software has still chosen to implement it on their own. Thus, Samourai Wallet has developed its own implementation of BIP47: PayNym. Today, this implementation is obviously available on Samourai Wallet for smartphones, but also on Sparrow Wallet for PCs.

Over time, Samourai has programmed new features directly related to PayNym. Now, there is an ecosystem of tools to optimize user privacy based on PayNym and BIP47.

In this article, you will learn about the principle of BIP47 and PayNym, the mechanisms of these protocols and the practical applications that result from them. I’m only going to talk about the first version of the BIP47, the one currently used for PayNym, but versions 2, 3 and 4 work practically the same way.

The only major difference is in the notification transaction. Version 1 uses a simple address with the OP_RETURN for notification, version 2 uses a multisig script (bloom-multisig) with the OP_RETURN and version 3 and 4 simply use a multisig script (cfilter-multisig). The mechanisms mentioned in this article, and in particular the cryptographic methods studied, are therefore applicable to the four versions. To date, the PayNym implementation on Samourai Wallet and Sparrow uses the first version of BIP47.

The problem of address reuse #

A receiving address is used to receive bitcoins. It is generated from a public key by hashing it and applying a specific format to it. Thus, it makes it possible to create a new condition of expenditure on a room in order to modify its owner.

Moreover, you have probably already heard from a well-informed bitcoiner that reception addresses are for one-time use, and therefore it is necessary to generate a new one for any new payment entering your portfolio. Okay, but why?

Basically, address reuse does not directly endanger your funds. The use of cryptography on elliptic curves can prove to the network that you are in possession of a private key without revealing this key. So you can block several different UTXO on the same address and spend them at different times. If you do not reveal the private key associated with this address, no one will be able to access your funds. The problem of address reuse is rather one of privacy.

As mentioned in the introduction, the transparency and distribution of the Bitcoin network means that any user, provided they have access to a node, is able to observe the transactions of the payment system. As a result, he can see the different balances of the addresses. Satoshi Nakamoto then mentioned the possibility of generating new key pairs, and thus new addresses, for any new payment entering a wallet. The goal would be to have an additional firewall in case of an association between the user’s identity and one of his key pairs.

Today, with the presence of chain analysis companies and the development of KYC, the use of blank addresses is no longer an additional firewall, but an obligation for anyone who cares a minimum about their privacy.

The search for privacy is not a comfort or a maximalist bitcoiner’s fantasy. This is a specific parameter that directly affects your personal security and the security of your funds. To make you understand, here is a very concrete example:

- Bob buys bitcoin in DCA (Dollars Cost Average), that is, he acquires a small amount of bitcoins at regular intervals in order to smooth his entry price. Bob systematically sends the purchased funds to the same receiving address. He buys 0.01 bitcoin every week and sends them to that same address. After two years, Bob accumulated an entire bitcoin on this address.

- The baker around the corner accepts payments in bitcoins. Happy to be able to spend bitcoins, Bob goes to buy his wand in sats. To pay, he uses the blocked funds with his address. His baker now knows that he owns a bitcoin. This large sum could make people envious, and Bob could potentially suffer a physical attack afterwards.

Address reuse therefore allows an observer to make an undeniable link between your different UTXO, and therefore sometimes, between your identity and your entire portfolio.

It is for this reason that the majority of Bitcoin wallet software automatically generates a new receiving address for you when you click on the “Receive” button. For the regular user, getting into the habit of using blank addresses is therefore not a great disadvantage. On the other hand, for an online business, an exchange or a donation campaign, this constraint can quickly become unmanageable.

There are many solutions for these organizations. Each of them has its advantages and disadvantages, but to date, and as we will see later, the BIP47 really differs from the others.

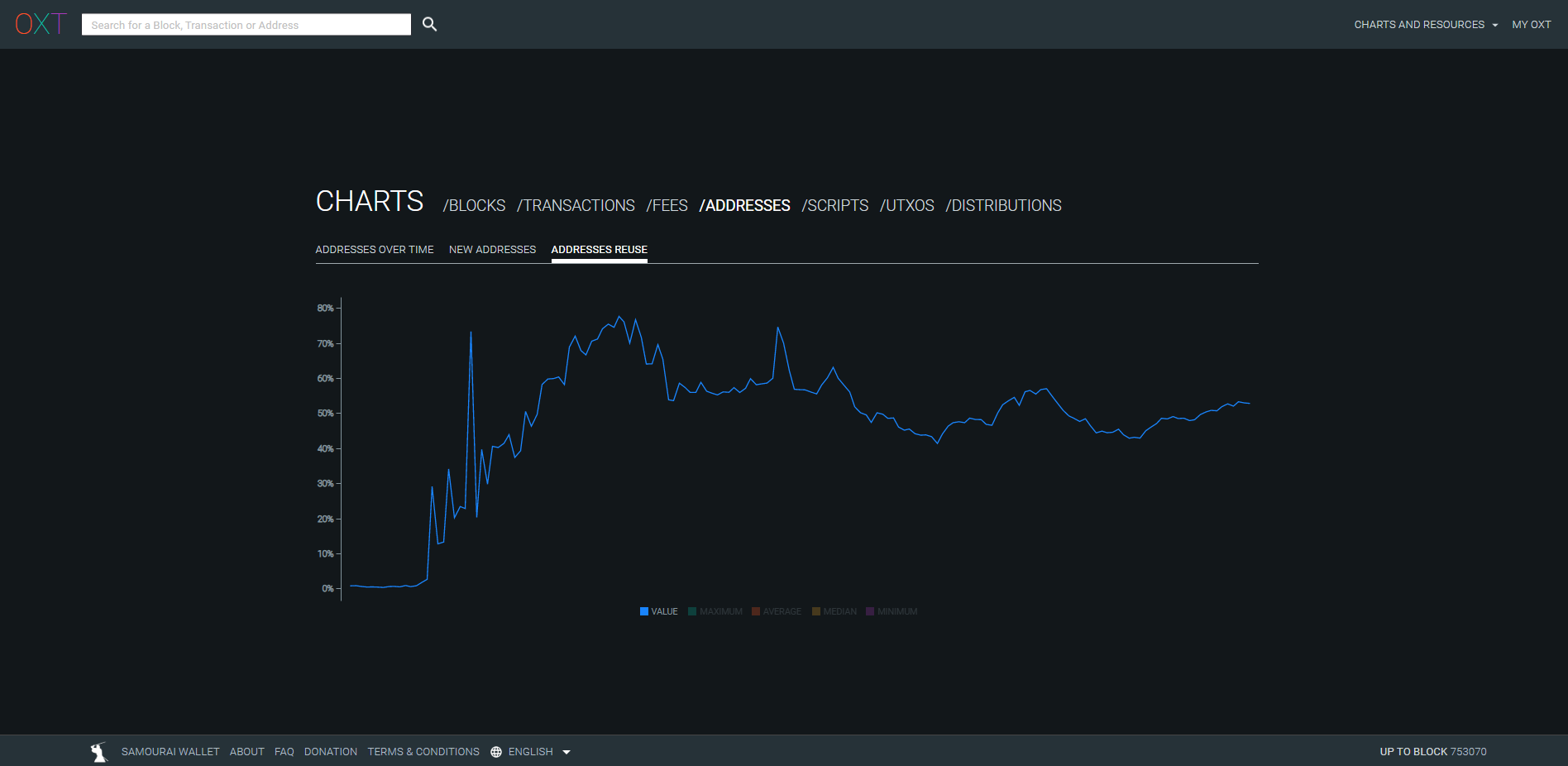

This problem of address reuse is far from negligible on Bitcoin. As you can see in the graph below taken from the oxt.me site, the overall address reuse rate by Bitcoin users is currently 52%:

Credit: https://oxt.me/charts

The majority of these reuses come from exchanges that, for reasons of efficiency and ease, reuse the same address many times. To date, BIP47 would be the best solution to stem this phenomenon in exchanges. This would make it possible to reduce this overall rate of address reuse, without causing too much friction for these entities. This overall measurement over the entire network is a particularly consistent data in this case. Indeed, address reuse is not only a problem for the person who performs this type of practice, but also for anyone who carries out transactions with it. The loss of privacy on Bitcoin acts as a virus, and spreads from user to user. Studying a global measure on all network transactions allows us to become aware of the magnitude of this phenomenon.

Principles of BIP47 and PayNym #

BIP47 aims to offer a simple way to receive many payments while not doing address reuse. Its operation is based on the use of a reusable payment code.

Thus, multiple issuers will be able to send multiple payments to a single reusable payment code of another user, without the recipient having to transmit a new blank address for each new transaction.

A user can then freely communicate his payment code (on social networks, on his website…) without risk of loss of confidentiality, unlike a classic reception address or a public key.

To make an exchange, both users will need to have a Bitcoin wallet with an implementation of BIP47, such as PayNym on Samourai Wallet or Sparrow Wallet. The association of the payment codes of the two users will make it possible to establish a secret channel between them. To properly establish this channel, the issuer will have to carry out a transaction on the Bitcoin chain: the notification transaction (I will tell you a little more about it).

The association of the payment codes of the two users generates shared secrets allowing themselves to generate a large number of unique Bitcoin receiving addresses (2^32 exactly). Thus, in reality, the payment with BIP47 is not sent to the payment code, but to quite classic addresses, themselves derived from the payment codes of the protagonists.

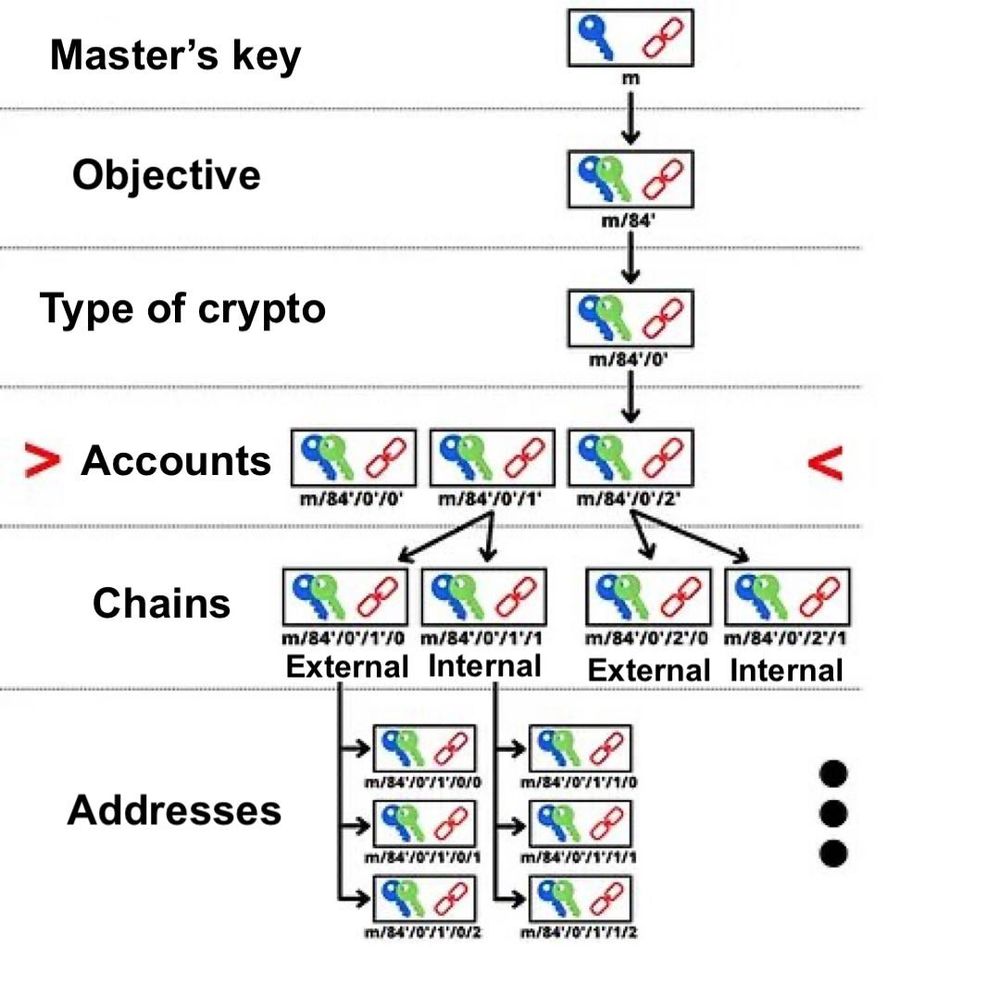

The payment code therefore acts as a virtual identifier, derived from the seed of the wallet. In the DErivation structure of the HD wallet, the payment code is found in depth 3, at the level of the wallet accounts.

Its derivation objective is noted 47’ (0x8000002F) in reference to BIP47. A derivation path of a reusable payment code will be for example:

m/47'/0'/0'/

So you can imagine what a payment code looks like, here’s mine:

PM8TJSBiQmNQDwTogMAbyqJe2PE2kQXjtgh88MRTxsrnHC8zpEtJ8j7Aj628oUFk8X6P5rJ7P5qDudE4Hwq9JXSRzGcZJbdJAjM9oVQ1UKU5j2nr7VR5

It can also be encoded in QRcode to facilitate communication:

As for PayNym Bots, these robots that can be seen on Twitter, they are simply visual representations of your payment code, made by Samourai Wallet. They are created through a hash function, which makes them unique. Here is mine with its identifier:

+throbbingpond8B1

These Bots have no real technical use. Instead, they facilitate interactions between users by creating a virtual visual identity.

For the user, the process of a BIP47 payment with the PayNym implementation is extremely simple. Let’s say Alice wants to send payments to Bob:

- Bob broadcasts his QR code, or directly his reusable payment code. He can place it on his website, on his various public social networks or send it to Alice through another means of communication. :

- Alice opens her Samourai or Sparrow software, and scans, or pastes, Bob’s payment code.

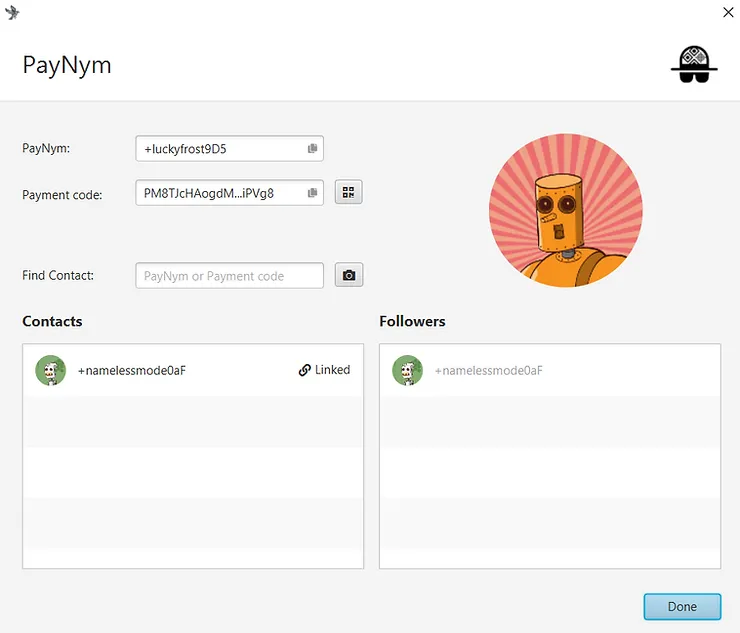

- Alice connects her PayNym with Bob’s (“Follow”). This operation is done outside the blockchain and remains completely free.

- Alice connects her PayNym with Bob’s (“Connect”). This operation is done “on chain”. Alice must pay the transaction mining fee as well as a fixed fee of 15,000 sats for the service on Samourai. Service fees are available on Sparrow. This step is called the notification transaction.

- Once the notification transaction is confirmed, Alice can create a BIP47 payment transaction to Bob. His wallet will automatically generate a new blank receiving address for which only Bob has the private key.

Completing the notification transaction, i.e. connecting your PayNym, is a mandatory preliminary step to make BIP47 payments. On the other hand, once it is done, the sender will be able to make multiple payments to the recipient (2^32 exactly), without the need to carry out a notification transaction again.

You could see that there are two different operations that allow PayNym to be linked together: link and connect. The connection operation (“connect”) corresponds to the notification transaction of the BIP47 which is simply a Bitcoin transaction with certain information transmitted through a OP_RETURN output. Thus, it helps to establish encrypted communication between the two users in order to produce the shared secrets needed to generate new blank receiving addresses.

On the other hand, the link operation (“follow” or “link”) makes it possible to establish a link on Soroban, an encrypted communication protocol based on Tor, specially developed by the Samourai teams.

To summarize:

- Linking two PayNym (“follow”) is totally free. This helps to establish encrypted “off chain” communications, in particular in order to use Samourai’s collaborative transaction tools (Stowaway or StonewallX2). This operation is specific to PayNym. It is not described in BIP47.

- Connecting two PayNym is chargeable. This involves performing the notify transaction in order to initiate the connection. Its cost is made up of any service fees, transaction mining fees and 546 sats sent to the recipient’s notification address to notify them of the opening of the tunnel. This operation is related to BIP47. Once done, the sender can make several BIP47 payments to the recipient.

In order to connect two PayNyms, they must already be connected.

Tutorials: Using PayNym #

Now that we have seen the theory, let’s study the practice together. The idea of the tutorials below is to link my PayNym on my Sparrow wallet with my PayNym on my Samourai wallet. The first tutorial shows you how to make a transaction using the reusable payment code from Samourai to Sparrow, and the second tutorial describes the same mechanism from Sparrow to Samourai.

I did these tutorials on the Testnet. These are not real bitcoins.

Build a BIP47 transaction with Samourai Wallet. #

For starters, you’re obviously going to need the Samourai Wallet app. You can download it directly from the Google Play Store, or with the APK file available on the official website of Samourai.

Once the wallet is initialized, if you have not already done so, request your PayNym by clicking on the plus (+) at the bottom right, then on “PayNym”.

The first step to making a BIP47 payment is going to be to retrieve our recipient’s reusable payment code. Then, we will be able to connect with it, and then connect:

Once the notification transaction is confirmed, I can send multiple payments to my recipient. Each transaction will be done automatically with a new blank address for which the recipient has the keys. The latter has no action to perform, everything is calculated on my side.

Here’s how to make a BIP47 transaction on Samourai Wallet:

Build a BIP47 transaction with Sparrow Wallet #

In the same way as for Samourai, you must obviously have the Sparrow software. It is available on computer. You can download it from their official website.

Remember to check the developer’s signature and the integrity of the downloaded software before installing it on your machine.

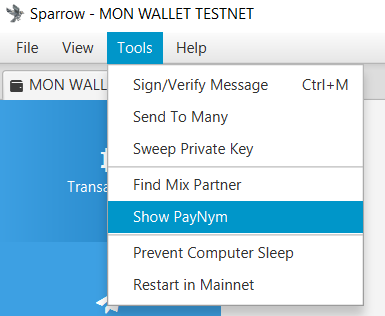

Create a wallet and request your PayNym by clicking on “Show PayNym” from the “Tool” menu in the top bar:

Next, you’ll need to link and connect your PayNym with your recipient’s. To do this, enter its reusable payment code in the “Find Contact” window, follow it, then complete the notification transaction by clicking on “Link Contact”:

Once the notification transaction is confirmed, payments can be sent to the reusable payment code. Here’s how to do it:

Now that we have been able to study the practicality of the PayNym implementation of BIP47, let’s see together how all these mechanisms work, and what cryptographic methods are used.

The workings of the BIP47 #

The reusable payment code. #

As explained in the second part of this paper, the reusable payment code is found in depth three of the HD wallet. It is finally somewhat comparable to an xpub, as much in its placement and structure as in its role.

Here are the different parts that make up an 80-byte payment code:

- Byte 0: The version. If we use the first version of BIP47 then this byte will be equal to 0x01.

- Byte 1: The bit field. This space is reserved to give additional indications in case of specific use. If one simply uses PayNym, this byte will be equal to 0x00.

- Byte 2: The parity of y. This byte indicates 0x02 or 0x03 depending on the parity (even number or odd number) of the value of the ordinate of our public key.

- From byte 3 to byte 34: The value of x. These bytes indicate the abscissa of our public key. The concatenation of x and the parity of y gives us our compressed public key.

- From byte 35 to byte 66: The string code. This space is reserved for the string code associated with the aforementioned public key.

- From byte 67 to byte 79: Padding. This space is reserved for possible future developments. For version 1 we simply put zeros to fill up to 80 bytes, the size of the data of an output OP_RETURN.

Here is the hexadecimal representation of my reusable payment code, shown in the previous part, with the colors corresponding to the bytes shown above:

0x010002a0716529bae6b36c5c9aa518a52f9c828b46ad8d907747f0d09dcd4d9a39e97c3c5f37c470c390d842f364086362f6122f412e2b0c7e7fc6e32287e364a7a36a00000000000000000000000000

Then, we must also add the byte of the prefix “P” to identify at a glance that we are dealing with a payment code. This byte is 0x47.

0x47010002a0716529bae6b36c5c9aa518a52f9c828b46ad8d907747f0d09dcd4d9a39e97c3c5f37c470c390d842f364086362f6122f412e2b0c7e7fc6e32287e364a7a36a00000000000000000000000000

Finally, we calculate the checksum of this payment code with HASH256, that is to say a double hash with the SHA256 function. We retrieve the first four bytes of this condensate and concatenate them at the end (in pink).

0x47010002a0716529bae6b36c5c9aa518a52f9c828b46ad8d907747f0d09dcd4d9a39e97c3c5f37c470c390d842f364086362f6122f412e2b0c7e7fc6e32287e364a7a36a00000000000000000000000000567080c4

The payment code is ready, all that remains is to convert it to Base 58:

PM8TJSBiQmNQDwTogMAbyqJe2PE2kQXjtgh88MRTxsrnHC8zpEtJ8j7Aj628oUFk8X6P5rJ7P5qDudE4Hwq9JXSRzGcZJbdJAjM9oVQ1UKU5j2nr7VR5

As you can notice, this construction strongly resembles the structure of an extended public key of type “xpub”.

During this process to arrive at our payment code, we used a compressed public key and a string code. These two elements are the result of a deterministic and hierarchical derivation, from the seed of the portfolio, following the following derivation path: m/47’/0’/0’/.

Concretely, to obtain the public key and the chain code of the reusable payment code, we will calculate the master private key from the seed, then derive a child pair with the index 47 + 2^31 (hardened derivation). Then, we derive two child pairs with the index 2^31 (hardened derivation).

The cryptographic method: the Diffie-Hellman key exchange established on elliptic curves (ECDH) #

The cryptographic method used at the base of BIP47 is ECDH (Elliptic-Curve Diffie-Hellman = Diffie-Hellman key exchange established on elliptic curves). This protocol is a variant of the classic Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

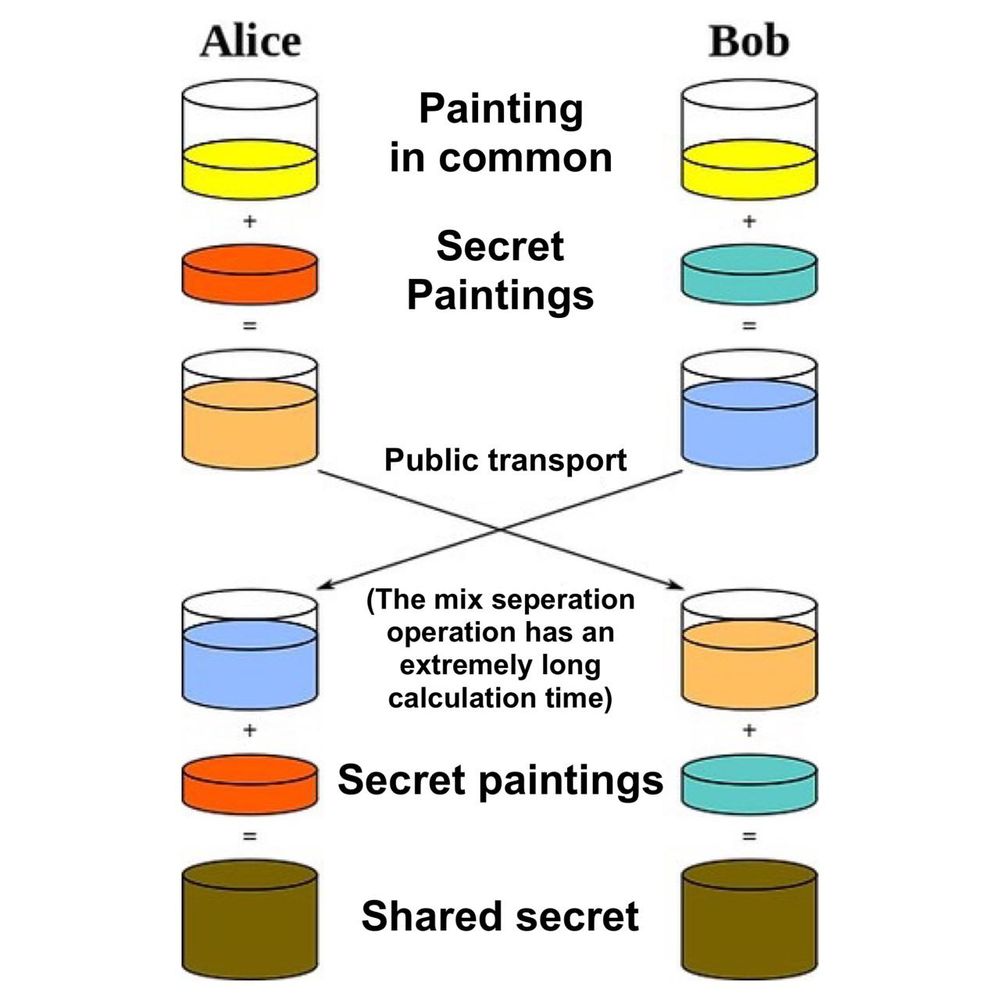

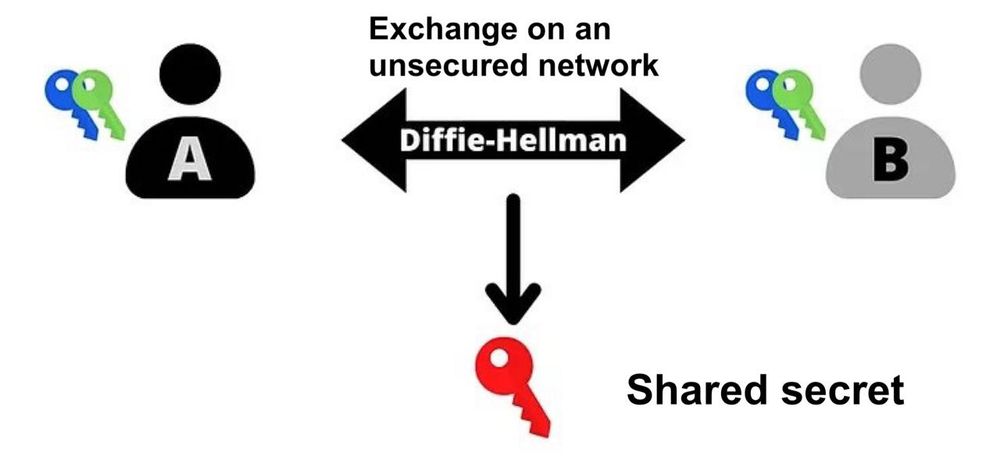

Diffie-Hellman, in its first version, is a key memorandum of understanding presented in 1976 that allows two people, from two pairs (public keys and private keys), to determine a shared secret by exchanging on an unsecured communication channel.

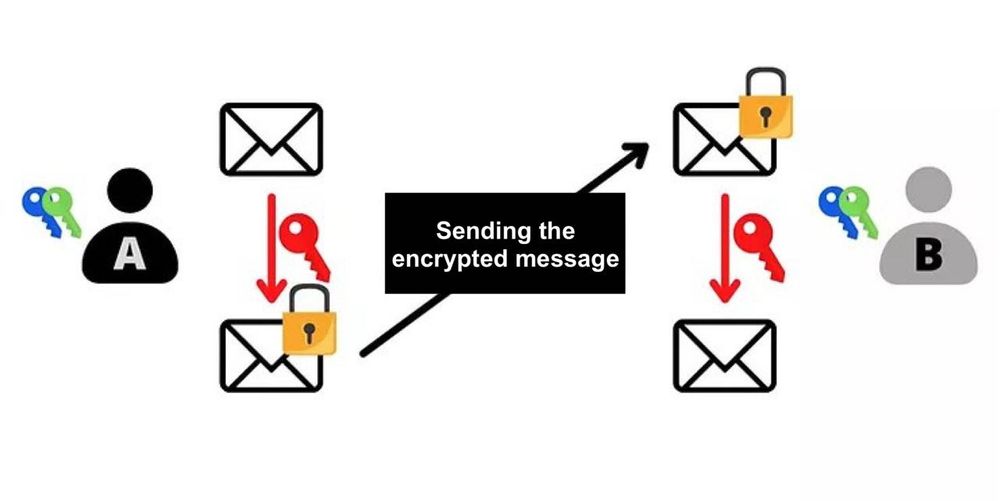

This shared secret (the red key) can then be used to perform other tasks. Typically, this shared secret can be used to encrypt and decrypt a communication over an unsecured network:

To succeed in this exchange, Diffie-Hellman uses modular arithmetic to calculate the common secret. Here is its popularized operation:

- Alice and Bob determine a common color, here yellow. This color is known to all. It is a public data

- Alice chose a secret color, here red. It mixes the two colors which gives it orange.

- Bob chose a secret color, here duck blue. It mixes the two colors which gives it sky blue.

- Alice and Bob can exchange the colors obtained: orange and sky blue. This exchange can be done on an unsecured network and observed by attackers.

- Alice mixes the sky blue color received from Bob with her secret color (red). She gets brown.

- Bob mixes the orange color received from Alice with his secret color (duck blue). It gets that same brown color.

In this popularization, the color brown represents the secret shared between Alice and Bob. We must imagine that in reality, it is impossible for the attacker to separate the colors orange and sky blue, in order to find the secret colors of Alice or Bob.

Now, let’s study how it actually works. At first glance, Diffie-Hellman seems complex to grasp. In reality, the principle of operation is almost childish. Before detailing its mechanisms, I quickly remind you of two mathematical notions that we will need (and which incidentally, are also used in many other cryptographic methods).

- A prime number is a natural number that admits only two divisors: 1 and itself. For example, the number 7 is prime, because it can only be divided by 1 and 7 (itself). On the other hand, the number 8 is not prime, because it can be divided by 1, 2, 4 and 8. It therefore admits not only two divisors, but four integer and positive divisors.

- The “modulo” (denoted “mod” or “%”) is a mathematical operation that allows between two integers to return the rest of the Euclidean division of the first by the second number. For example, 16 mod 5 is equal to 1.

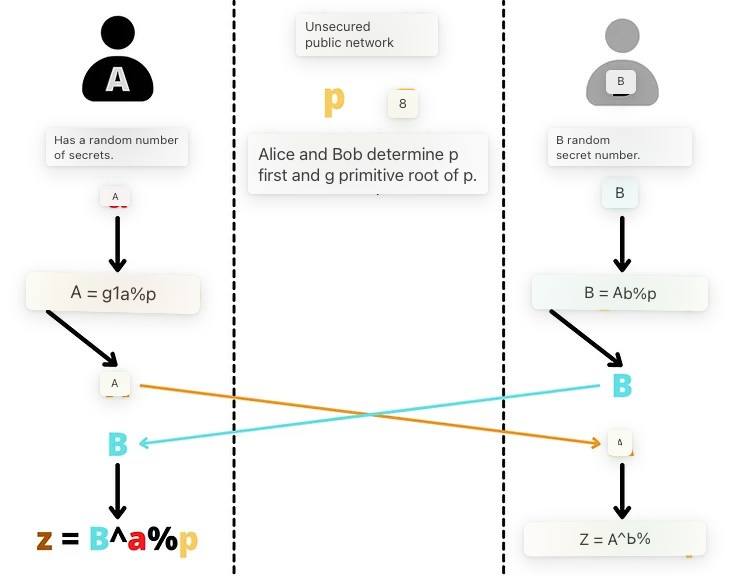

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange between Alice and Bob works like this:

- Alice and Bob determine two common numbers: p and g. p is a prime number. The larger this p-number, the more secure Diffie-Hellman will be. g is a primitive root of p. These two numbers can be communicated in clear on an unsecured network, they are the equivalents of the yellow color in the popularization above. Alice and Bob just have to have exactly the same p and g values.

- Once the parameters are chosen, Alice and Bob each determine a secret random number. The random number obtained by Alice is named a (equivalent to the color red) and the random number obtained by Bob is named b (equivalent to the color blue duck). These two numbers must remain secret.

- Instead of exchanging these numbers a and b, each part will calculate A (uppercase) and B (uppercase) such as:

# A is equal to g power a modulo p:

A = g^a % p

# B is equal g power b modulo p:

B = g^b % p

- These numbers A (equivalent to the orange color) and B (equivalent to the sky blue color) will be exchanged between the two parties. The exchange can be done in the clear on an unsecured network.

- Alice, who is now in knowledge of B, will calculate the value of z such that:

# z is equal to B power a modulo p:

z = B^a % p

- As a reminder, B = g^b % p. So we have:

z = B^a % p

z = (g^b)^a % p

# According to the calculation rules on powers:

(x^n)^m = x^nm

# So we have:

z = g^ba % p

- Bob, who is now aware of A, will also calculate the value of z such that:

# z is equal to A power b modulo p:

z = A^b % p

# So we have:

z = (g^a)^b % p

z = g^ab % p

z = g^ba % p

Thanks in particular to the distributivity of the modulo operator, Alice and Bob find exactly the same z-value. This number represents their common secret, that is, the equivalent of the brown color in the previous popularization. They can use this common secret to encrypt a communication between the two of them on an unsecured network.

An attacker in possession of p, g, A and B will be unable to calculate a, b or z. To do this would be to reverse the exponentiation. This calculation is impossible to achieve other than by trying all the possibilities one by one since we are working on a finite field. This would be equivalent to calculating the discrete logarithm, i.e. the reciprocal of the exponential in a finite cyclic group.

Thus, as long as one chooses a, b and p large enough, Diffie-Hellman is secure. Typically, with parameters of 2,048 bits (number of 600 digits in decimal), testing all the possibilities for a and b would be chimerical. To date, with numbers of this size, the algorithm is considered safe.

It is precisely at this level that the main disadvantage of the Diffie-Hellman protocol lies. To be secure, the algorithm must use large numbers. As a result, we prefer today to use the ECDH algorithm, a Diffie-Hellman variant using an algebraic curve, and in this case, an elliptic curve. This will allow us to work on much smaller numbers while maintaining equivalent security, and thus reduce the resources required for computing and storage.

The general principle of the algorithm remains the same. But, instead of using a random number a and a number A calculated since a with modular exponentiation, we will use a pair of keys established on an elliptic curve. Instead of relying on the distributivity of the modulo operator, we will use here the group law on elliptic curves, and more precisely the associativity of this law.

To summarize roughly, a private key is a random number between 1 and n-1 (n being the order of the curve), and a public key is a single point on the curve determined by the private key by adding and doubling points from the generating point such that:

K = k·G

Where K is the public key, k is the private key, and G is the generating point.

One of the properties of this key pair is that it is very easy to determine K by having knowledge of k and G, but today it is impossible to determine k by having knowledge of K and G. It is a one-way function.

In other words, one can easily calculate the public key with knowledge of the private key, but it is impossible to calculate the private key with knowledge of the public key. This security is again based on the impossibility of calculating the discrete logarithm.

We will therefore use this property to adapt our Diffie-Hellman algorithm. Thus, the principle of operation of ECDH is as follows:

- Alice and Bob agree together on a cryptographically safe elliptic curve and its parameters. This information is public.

- Alice generates a random number ka which will be her private key. This private key must remain secret. It determines its public key Ka by adding and doubling points on the chosen elliptic curve.

Ka = ka·G

- Bob also generates a random number that will be his kb private key. And, it calculates the associated public key Kb.

Kb = kb·G

- Alice and Bob exchange their Ka and Kb public keys on an unsecured public network.

- Alice calculates a point (x,y) on the curve by applying her private key ka from Bob’s Kb public key.

(x,y) = ka·Kb

- Bob calculates a point (x,y) on the curve by applying his kb private key from Alice’s Ka public key.

(x,y) = kb·Ka

- Alice and Bob get the same point on the elliptic curve. The shared secret will be the x-ray of this point.

They get the same shared secret because:

(x,y) = ka·Kb = ka·kb·G = kb·ka·G = kb·Ka

A potential attacker who observes the unsecured public network will only be able to obtain the public keys of each and the parameters of the chosen curve. As explained earlier, these two pieces of information alone do not determine the private keys, and therefore the attacker cannot access the secret.

ECDH is therefore an algorithm allowing an exchange of keys. It will often be used alongside other cryptographic methods to define a protocol. For example, ECDH is used at the heart of Transport Layer Security (TLS), an encryption and authentication protocol used for the transport layer of the Internet. TLS uses ECDHE for key exchange, a variant of ECDH where keys are ephemeral in order to provide persistent privacy. In addition to the latter, TLS also uses an authentication algorithm like ECDSA, an encryption algorithm like AES, and a hash function like SHA256.

TLS defined in particular the “s” in “https”, as well as the small padlock that you see on your internet browser at the top left, which guarantee you an encryption of the communication. So you are using ECDH while reading this article, and you probably use it daily without realizing it.

The notification transaction #

As we discovered in the previous part, ECDH is a variant of the Diffie-Hellman exchange involving key pairs established on an elliptic curve. That’s good, key pairs respecting this standard, we have plenty of our Bitcoin wallets!

The idea will therefore be to use the key pairs of the hierarchical Deterministic Bitcoin wallets of the two stakeholders to establish shared and ephemeral secrets between them. Within the BIP47, we use ECDHE (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral).

ECDHE is used for the first time in BIP47 to transmit the payment code from the sender to the recipient. This is the famous notification transaction. Indeed, for BIP47 to be used, it is necessary that each of the two parties (the sender who sends payments, and the recipient who receives payments) are aware of the payment code of the other party. This will be necessary to derive ephemeral public keys, and therefore dedicated receiving addresses.

Before this exchange, the sender is logically already aware of the recipient’s payment code since he was able to retrieve it off-chain, for example, on his website or on his social networks. On the other hand, the recipient is not necessarily aware of the sender’s payment code. It will be necessary to transmit it to him, otherwise he will not be able to derive his ephemeral keys, and therefore he will be unable to know where his bitcoins are and to unlock his funds. It could thus be transmitted to him off-chain, with another communication system, but this would pose a problem in case of recovery of the wallet from the seed.

Indeed, as I have already mentioned, BIP47 addresses are not derived from the recipient’s seed (otherwise use one of his xpub directly), but are the result of a calculation involving the two payment codes: that of the recipient and that of the sender. That is why, if the recipient loses his wallet and tries to recover it from his seed, he will necessarily have to have all the payment codes of the people who sent him bitcoins via BIP47.

We could therefore easily use the BIP47 without this notification transaction, but each user would have to make a backup of the payment codes of his peers. This situation will remain unmanageable until a simple and resilient way to perform, store and maintain these backups is found. The notification transaction is therefore almost mandatory in the current state of affairs.

In addition to this role of saving payment codes, as the name suggests, this transaction also plays a role of notification of the recipient. It allows you to inform your customer that a tunnel has just been opened.

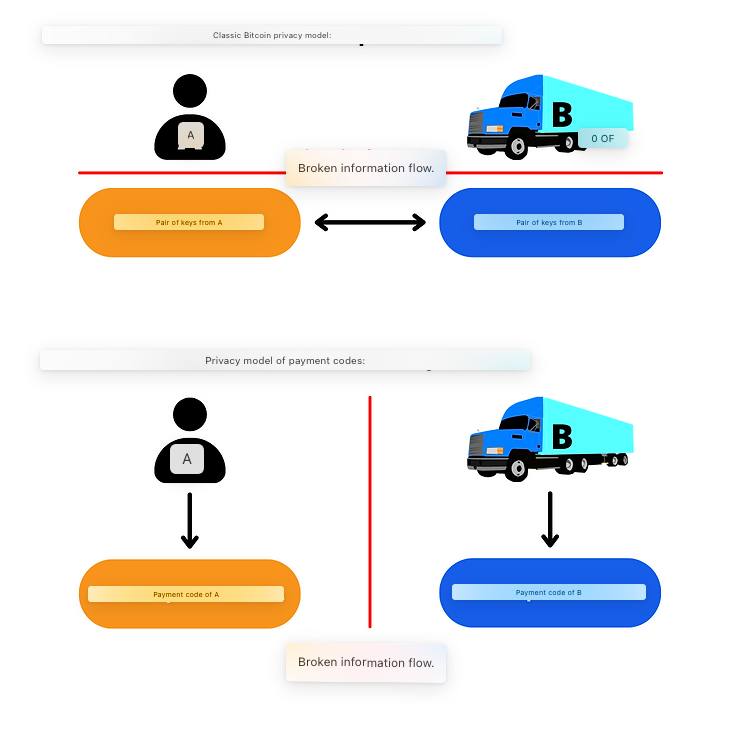

Before I explain in more detail the technical operation of the notification transaction, I want to tell you a little about the privacy model. Indeed, that of the BIP47 will justify certain precautions taken during the construction of this initial transaction.

The payment code itself does not directly constitute a risk of loss of confidentiality. Unlike Bitcoin’s classic model, which breaks the flow of information between the user’s identity and transactions, including keeping public keys anonymous, the payment code can be directly associated with an identity. This is obviously not an obligation, but this link is not dangerous.

Indeed, the payment code does not directly derive from the addresses used to receive BIP47 payments. Instead, addresses are obtained by applying ECDHE between child keys of both parties’ payment codes.

A payment code alone does not therefore constitute a direct risk of loss of confidentiality since only the notification address is derived from it. We can draw some information from it, but we will not normally be able to know with whom you are making transactions.

It is therefore essential to maintain this strict separation between users’ payment codes. To this end, the initial communication stage of the code is a critical moment for the confidentiality of the payment, and yet mandatory for the proper functioning of the protocol. If one of the two payment codes can be retrieved publicly (for example, on a website), the second code, i.e. that of the sender, must not be associated with the first.

For example, let’s say I want to donate with BIP47 to a peaceful protest movement in Canada:

- This organization has published its payment code directly on its website or on its social networks.

- This code is therefore associated with movement.

- I get this payment code back.

- Before I can send them a transaction, I need to make sure they are aware of my personal payment code which is also associated with my identity since I use it to receive transactions from my social networks.

How can I pass it on to them? If I send them with a conventional means of communication, the information may leak, and I risk being registered as a person who supports peaceful movements.

The notification transaction is certainly not the only solution to transmit the sender’s payment code secretly, but it fulfills for the moment perfectly this role by applying several layers of security.

In the diagram below, the red lines represent when the flow of information must be broken, and the black arrows represent the undeniable links that can be made by an outside observer:

In reality, for Bitcoin’s classic privacy model, it is often difficult to completely break the flow of information between the key pair and the user, especially when making transactions remotely. For example, in the case of a donation campaign, the recipient will be obliged to reveal an address or public key on their website or social networks. The own use of the BIP47, that is to say with the notification transaction, makes it possible to solve this thanks to ECDHE and the encryption layer that we will study.

Obviously, bitcoin’s classic privacy model is still observed at the level of ephemeral public keys derived from the association of the two payment codes. The two models are interdependent. I just want to highlight here that, unlike the classic use of a public key to receive bitcoins, the payment code can be associated with an identity, because the information “Bob makes a transaction with Alice” is broken at another time. The payment code is used to generate payment addresses, but by observing only the blockchain, it is impossible to associate a BIP47 payment transaction with the payment codes used to carry it out.

Construction of the notification transaction #

Now, let’s see how this notification transaction works. Let’s say Alice wants to send money to Bob with BIP47. In my example, Alice acts as the sender and Bob as the recipient. The latter has published its payment code on its website. Alice is already aware of Bob’s payment code.

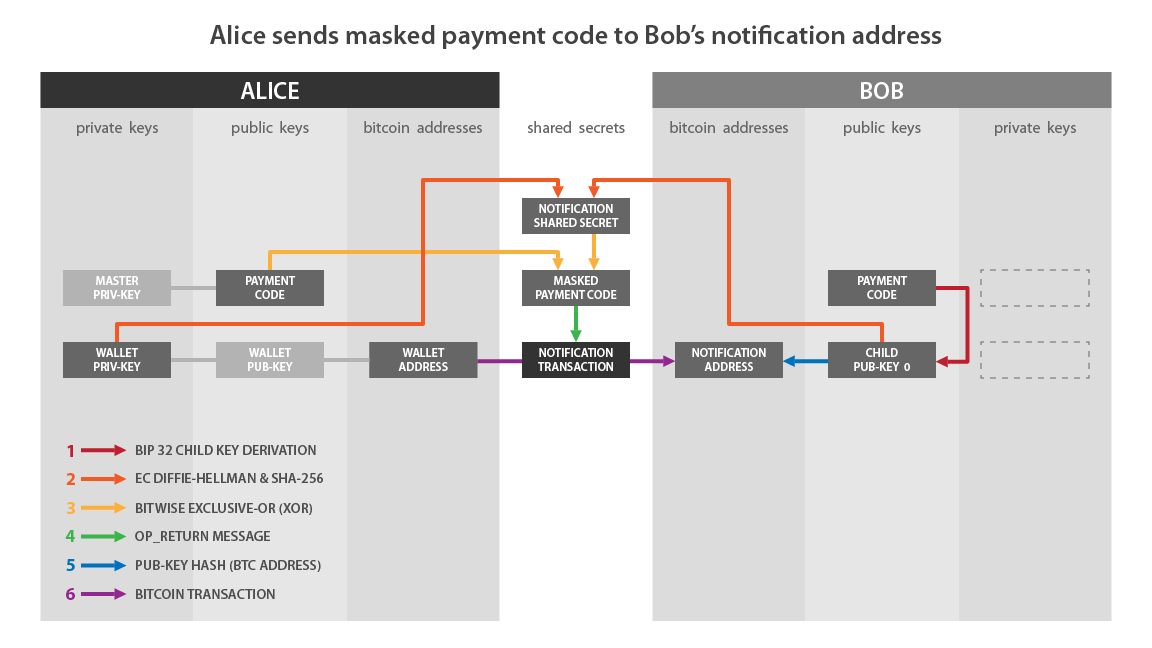

- Alice calculates a secret shared with ECDH:

- It selects a key pair within its HD wallet that is on a different branch of its payment code. Be careful, this pair should not be easily associated with Alice’s notification address, nor with Alice’s identity (see previous part).

- Alice selects the private key for this pair. We call it “a” (lowercase).

a

- Alice retrieves the public key associated with Bob’s notification address. This key is the first child key derived from Bob’s payment code (index 0). We name this public key “B” (uppercase). The private key associated with this public key is named “b” (lowercase). “B” is determined by adding and doubling points on the elliptic curve from “G” (the generating point) with “b” (the private key).

B = b·G

- Alice calculates a secret point “S” (uppercase) on the elliptic curve by adding and doubling points by applying her private key “a” from Bob “B’s” public key.

S = a·B

- Alice calculates the blinding factor “f” that will encrypt her payment code. For this, it will determine a pseudo-random number with the HMAC-SHA512 function. In the second entry of this function, it uses a value that only Bob will be able to find: (x) which is the abscissa of the secret point calculated previously. The first entry is (o) which is the UTXO consumed as input of this transaction (outpoint).

f = HMAC-SHA512(o, x)

Alice converts her personal payment code to base 2 (binary).

It uses this blinding factor as a key to perform symmetric encryption on the payload of its payment code. The encryption algorithm used is simply an XOR. The operation carried out is comparable to Vernam’s figure, also called the “disposable mask” (in English: “One-Time Pad”):

- Alice first separates her blinding factor in two: the first 32 bytes are named “f1” and the last 32 bytes are named “f2”. So we have:

f = f1 || f2

- Alice calculates the encrypted (x’) of the abscissa of the public key (x) of her payment code, and the encrypted (c’) of her string code (c) separately. “f1” and “f2” act as encryption keys, respectively. The operation used is the XOR (or exclusive).

x' = x XOR f1

c' = c XOR f2

- Alice replaces the actual values of the abscissa of the public key (x) and the string code (c) in her payment code with the encrypted values (x’) and (c’).

Before continuing the technical description of this notification transaction, let’s dwell for a few moments on this XOR operation. XOR is a bit-level logical operator based on Boolean algebra. From two operands in bits, it returns 1 if the bits of the same rank are different, and it returns 0 if the bits of the same rank are equal. Here is the truth table of the XOR according to the values of the operands D and E:

| D | E | D XOR E |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Like:

0110 XOR 1110 = 1000

Or:

010011 XOR 110110 = 100101

With ECDH, the use of XOR as an encryption layer is particularly consistent. First, thanks to this operator, the encryption is symmetric. This will allow the recipient to decrypt the payment code with the same key that enabled the encryption. The encryption and decryption key is calculated from the secret shared through ECDH.

This symmetry is allowed by the commutativity and associativity properties of the XOR operator:

# Other properties:

-> D ⊕ D = 0

-> D ⊕ 0 = D

# Commutativity:

D ⊕ E = E ⊕ D

# Associativity:

D ⊕ (E ⊕ Z) = (D ⊕ E) ⊕ Z = D ⊕ E ⊕ Z

# Symmetry:

Если: D ⊕ E = L

То: D ⊕ L = D ⊕ (D ⊕ E) = D ⊕ D ⊕ E = 0 ⊕ E = E

-> D ⊕ L = E

Second, this encryption method is very similar to the Vernam (One-Time Pad) cipher, the only known encryption algorithm to date that has unconditional (or absolute) security. For the Vernam cipher to have this characteristic, the encryption key must be perfectly random, be the same size as the message, and be used only once. In the encryption method used here for the BIP47, the key is indeed the same size as the message, the blinding factor is exactly the same size as the concatenation of the abscissa of the public key with the chain code of the payment code. This encryption key is used only once. On the other hand, this key is not the result of a perfect hazard since it is an HMAC. It is rather pseudo-random. So it’s not a Vernam number, but the method is getting closer.

Let’s go back to our construction of the notification transaction:

- Alice therefore currently has her payment code with an encrypted payload. It will build and distribute a transaction involving its public key “A” in input, an output to Bob’s notification address, and an output OP_RETURN consisting of its payment code with the encrypted payload. This transaction is the notification transaction.

the OP_RETURN is an Opcode, i.e. a script, which allows you to mark a Bitcoin transaction output as invalid. Today, it is used to disseminate or anchor information on the Bitcoin blockchain. It can store up to 80 bytes of data that are registered on the chain, and therefore visible to all other users.

As we saw in the previous part, Diffie-Hellman is used to generate a secret shared between two users who communicate over an unsecured network, and potentially observed by attackers. In the BIP47, ECDH is used to be able to communicate on the Bitcoin network, which by nature is a transparent communication network and observed by many attackers. The shared secret calculated through the Diffie-Hellman key exchange on the elliptic curve is then used to encrypt the secret information to be transmitted: the payment code of the sender (Alice).

Here is a diagram from BIP47 that illustrates what has just been described:

If we match this pattern with what I described earlier:

- “Wallet Priv-Key” on the Alice side corresponds to: a.

- “Child Pub-Key 0” on the Bob side corresponds to: B.

- “Notification Shared Secret” corresponds to: f.

- “Masked Payment Code” corresponds to the hidden payment code, i.e. with the encrypted payload: x’ and c’.

- “Notification Transaction” is the transaction that contains the OP_RETURN.

I summarize the steps that we have just seen together to carry out a notification transaction:

- Alice retrieves Bob’s payment code and notification address.

- Alice selects a UTXO that belongs to her on her HD wallet with the corresponding key pair.

- It calculates a secret point on the elliptic curve using ECDH.

- She uses this secret point to calculate an HMAC which is the blinding factor.

- She uses this blinding factor to encrypt the payload of her personal payment code.

- It uses a transaction output OP_RETURN to transfer the hidden payment code to Bob.

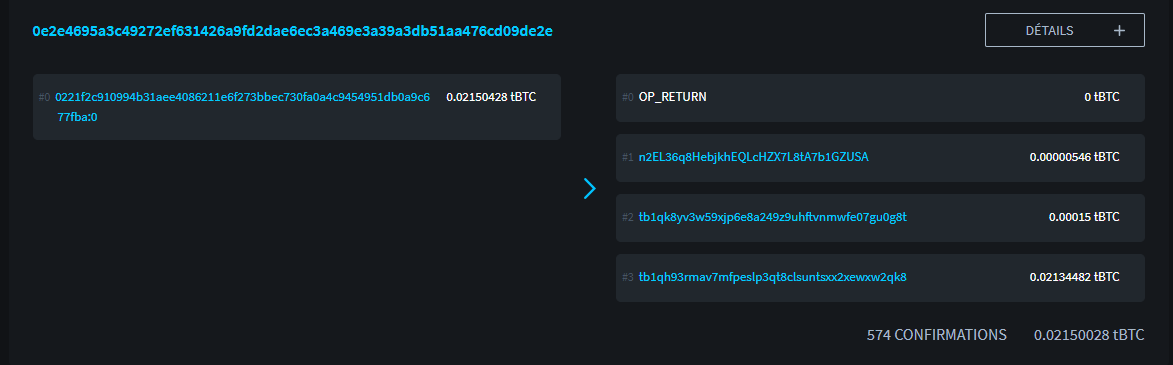

In order to understand in more detail how it works, and in particular the use of the OP_RETURN, let’s study together a real notification transaction. I made a transaction of this type on the Testnet that you can find by clicking here.

TXID:

0e2e4695a3c49272ef631426a9fd2dae6ec3a469e3a39a3db51aa476cd09de2e

Credit: https://blockstream.info/

By observing this transaction, we can already see that it has a single input and 4 outputs:

- The first output is the OP_RETURN which contains my hidden payment code.

- The second output of 546 sats points to my recipient’s notification address.

- The third output of 15,000 sats represents the service fee, because I used Samourai Wallet to build this transaction.

- The fourth output of two million sats represents the exchange rate, that is to say the remaining difference of my input that returns to another address belonging to me.

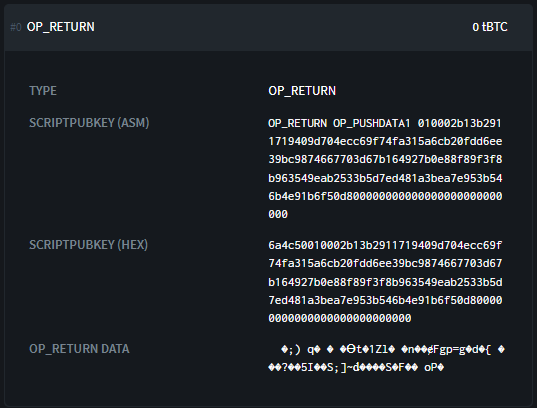

The most interesting to study is obviously the output 0 using the OP_RETURN. Let’s look in more detail at what it contains:

Credit: https://blockstream.info/

We discover the script of the output in hexadecimal:

6a4c50010002b13b2911719409d704ecc69f74fa315a6cb20fdd6ee39bc9874667703d67b164927b0e88f89f3f8b963549eab2533b5d7ed481a3bea7e953b546b4e91b6f50d800000000000000000000000000

In this script, we can dissect several parts:

6a4c50010002b13b2911719409d704ecc69f74fa315a6cb20fdd6ee39bc9874667703d67b164927b0e88f89f3f8b963549eab2533b5d7ed481a3bea7e953b546b4e91b6f50d800000000000000000000000000

Opcodes: 6a4c50

The metadata of my payment code in clear: 010002

The encrypted abscissa of the public key of my payment code: b13b2911719409d704ecc69f74fa315a6cb20fdd6ee39bc9874667703d67b164

The encrypted chain code of my payment code: 927b0e88f89f3f8b963549eab2533b5d7ed481a3bea7e953b546b4e91b6f50d8

Padding to get to 80 bytes: 00000000000000000000000000

Among the opcodes, we can recognize 0x6a which designates the OP_RETURN, 0x4c which designates the OP_PUSHDATA1 and 0x50 which designates the OP_RESERVED.

Then comes the payment code with the encrypted payload.

Here is my plaintext payment code used in this transaction:

- In base 58: PM8TJQCyt6ovbozreUCBrfKqmSVmTzJ5vjqse58LnBzKFFZTwny3KfCDdwTqAEYVasn11tTMPc2FJsFygFd3YzsHvwNXLEQNADgxeGnMK8Ugmin62TZU

- In base 16 (HEX): 4701000277507c9c17a89cfca2d3af554745d6c2db0e7f6b2721a3941a504933103cc42add94881210d6e752a9abc8a9fa0070e85184993c4f643f1121dd807dd556d1dc000000000000000000000000008604e4db

If we compare my payment code in clear with the OP_RETURN, we can see that the HRP (in brown) and the checksum (in pink) are not transmitted. This is normal, this information is intended for humans.

Then, we can recognize (in green) the version (0x01), the bit field (0x00) and the parity of the public key (0x02). And, at the end of the payment code, the empty bytes in black (0x00) that allow to padding to arrive at 80 bytes in total. All this metadata is transmitted in plain text (unencrypted).

Finally, it can be observed that the abscissa of the public key (in blue) and the string code (in red) have been encrypted. This is the payload of the payment code.

Receiving the notification transaction #

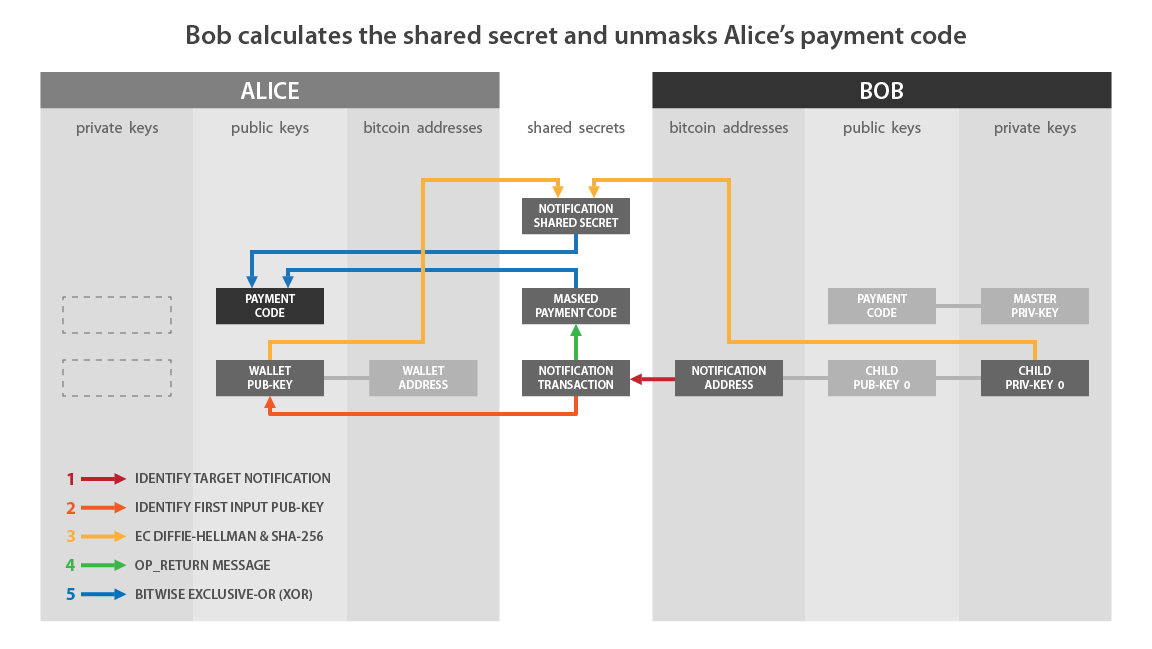

Now that Alice has sent the notification transaction to Bob, let’s see how Bob interprets it.

As a reminder, Bob must be able to access Alice’s payment code. Without this information, as we will see in the next part, he will not be able to derive the key pairs created by Alice, and therefore, he will not be able to access his bitcoins received with BIP47. At the moment, alice’s payment code payload is encrypted. Let’s see together how Bob deciphers it.

- Bob monitors transactions that create outputs with his notification address.

- When a transaction has an output on its notification address, Bob analyzes it to see if it contains output OP_RETURN that meets the BIP47 standard.

- If the first byte of the OP_RETURN’s payload is 0x01, Bob begins his search for a possible secret shared with ECDH:

- Bob selects the input public key for the transaction. That is, Alice’s public key named “A” with:

A = a·G

- Bob selects the private key “b” associated with his personal notification address:

b

- Bob calculates the secret point “S” (ECDH shared secret) on the elliptic curve by adding and doubling points by applying his private key “b” to Alice “A’s public key”:

S = b·A

- Bob determines the blinding factor “f” that will decipher the payload of Alice’s payment code. In the same way that Alice had calculated it previously, Bob will find “f” by applying HMAC-SHA512 on (x) the abscissa value of the secret point “S”, and on (o) the UTXO consumed as input of this notification transaction:

f = HMAC-SHA512(o, x)

- Bob interprets the OP_RETURN data in the notification transaction as a payment code. It will simply decipher the payload of this potential payment code thanks to the blinding factor “f”:

- Bob separates the blinding factor “f” into two parts: the first 32 bytes of “f” will be “f1” and the last 32 bytes will be “f2”.

- Bob decrypts the value of the encrypted abscissa (x’) of the public key of Alice’s payment code:

x = x' XOR f1

- Bob deciphers the value of the encrypted string code (c’) of Alice’s payment code:

c = c' XOR f2

- Bob checks to see if the public key value of Alice’s payment code is part of the secp256k1 group. If this is the case, he interprets it as a valid payment code. Otherwise, he ignores this transaction.

Now that Bob is aware of Alice’s payment code, she can send him up to 2^32 payments, without ever needing to redo a notification transaction of this type again.

Why does it work? How can Bob determine the same blinding factor as Alice, and thus decipher his payment code? Let us study in more detail the action of ECDH in what has just been described.

First of all, we are dealing with symmetric encryption. This means that the encryption key and the decryption key are the same value. This key in the notification transaction is the blinding factor (f = f1 || f2). Alice and Bob must therefore obtain the same value for f, without transmitting it directly since an attacker could steal it and decipher the secret information.

This blinding factor is obtained by applying HMAC-SHA512 on two values: the abscissa of a secret point and the UTXO consumed as input to the transaction. Bob must have these two pieces of information to decipher the payload of Alice’s payment code.

For the UTXO in input, Bob can simply retrieve it by observing the notification transaction. For the secret point, Bob will have to use ECDH.

As seen in the part about Diffie-Hellman, simply by exchanging their respective public keys, and secretly applying their private keys to each other’s public key, Alice and Bob can find a precise and secret point on the elliptic curve. The notification transaction is based on this mechanism:

# Bob's key pair:

B = b·G

# Alice's key pair:

A = a·G

# For a secret point S (x,y):

S = a·B = a·b·G = b·a·G = b·A

Now that Bob knows Alice’s payment code, he will be able to detect Alice’s BIP47 payments, and he will be able to derive the private keys blocking the bitcoins received.

If we match this pattern with what I described earlier:

- “Wallet Pub-Key” on the Alice side corresponds to: A.

- “Child Priv-Key 0” on the Bob side corresponds to: b.

- “Notification Shared Secret” corresponds to: f.

- “Masked Payment Code” corresponds to Alice’s hidden payment code, i.e. with the encrypted payload: x’ and c’.

- “Notification Transaction” is the transaction that contains the OP_RETURN.

I summarize the steps that we have just seen together to receive and interpret a notification transaction:

- Bob monitors transaction outputs to his notification address.

- When it detects one, it retrieves the information contained in the OP_RETURN.

- Bob selects the public key in input and calculates a secret point using ECDH.

- He uses this secret point to calculate an HMAC which is the blinding factor.

- He uses this blinding factor to decipher the payload of Alice’s payment code contained in the OP_RETURN.

The BIP47 payment transaction #

Now let’s study together the payment process with BIP47. To remind you of the current state of affairs:

- Alice is aware of the Bob payment code that she simply recovered on her website.

- Bob is knowing the Alice’s payment code thanks to the notification transaction.

- Alice will make a first payment to Bob. She can make many others in the same way.

Before explaining this process to you, I think it is important to recall what index we are currently working:

We describe the derivation path of a payment code like this: m/47’/0’/0’/.

The following depth distributes the indexes in this way:

- The first normal child key pair (not hardened) is that used to generate the notification address of which we have spoken in the previous part: m/47’/0’/0/0/.

- The pairs of normal child keys are used within ECDH to generate BIP47 payment reception addresses as we will see in this part: m/47’/0’/0’/ from 0 to 2 147 483 647/.

- The pairs of hardened child keys are ephemeral payment codes: m/47’/0’/0’/ from 0’ to 2 147 483 647’/.

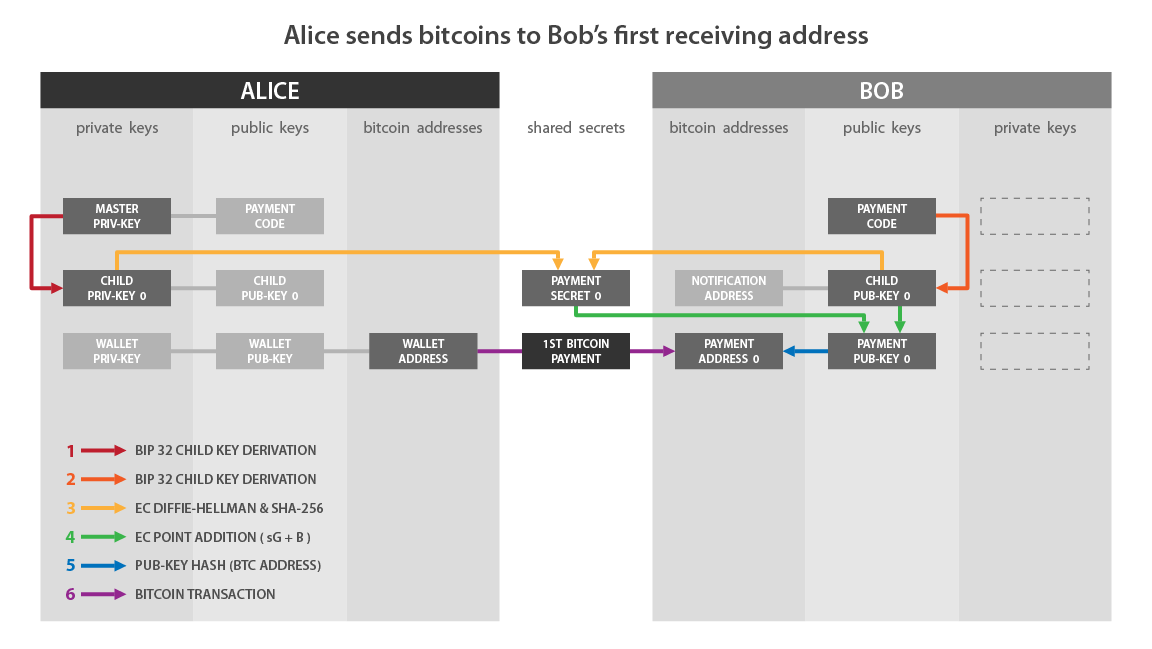

Whenever Alice wishes to send a payment to Bob, she derives a new unique virgin address, thanks once again to the ECDH protocol:

- Alice selects the first private key derived from her personal reusable payment code:

a

- Alice selects the first unused public key derived from Bob’s payment code. We’ll call this public key “B”. It is associated with the private key “b” known only to Bob.

B = b·G

- Alice calculates a secret point “S” on the elliptical curve by addition and doubling of points by applying her private key “A” from the public key of Bob “B”:

S = a·B

- From this secret point, Alice will calculate the shared secret “S” (tiny). To do this, she selects the abscissa from the secret point “S” named “SX”, and she passes this value in the hashness function sha256.

s = SHA256(Sx)

- Alice uses this shared secret “S” to calculate a Bitcoin payment reception address. At first, she verifies that “S” is well contained in the order of the SECP256K1 curve. If this is not the case, it increases the index of Bob’s public key in order to derive another shared secret.

- In a second step, it calculates a public key “K0” by adding on the elliptical curve the points “B” and “S · g”. In other words, Alice adds the public key derived from the Bob “B” payment code with another point calculated on the elliptical curve by adding and doubling of points with the shared secret “s” from the generating point of the SECP256K1 “G” curve. This new point represents a public key, and we call it “K0”:

K0 = B + s·G

- With this “K0” public key, Alice can derive a virgin reception address in a standard way (for example Segwit V0 in Bech32).

Once Alice has this “K0” reception address belonging to Bob, she can build a classic Bitcoin transaction, by selecting a UTXO which belongs to her on another branch of her HD portfolio, and spending towards the address " K0 “by Bob.

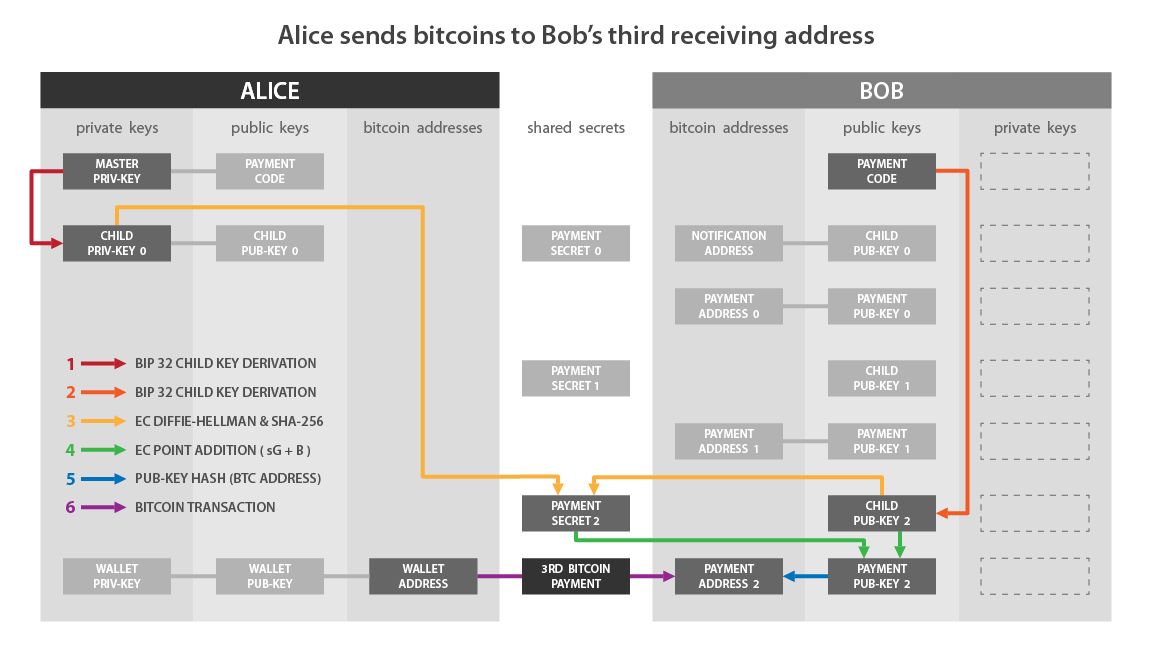

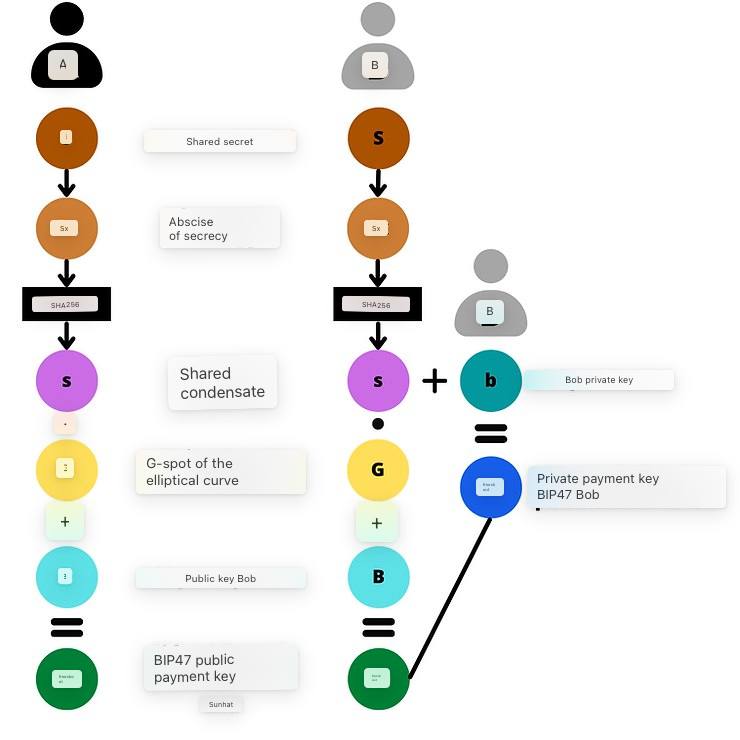

If we match this diagram with what I described to you previously:

- “Child Priv-Key” on the Alice side corresponds to: a.

- “Child Pub-Key 0” on the Bob side corresponds to: B.

- “Payment Secret 0” corresponds to: s.

- “Payment Pub-Key 0” corresponds to: K0.

I summarize the steps that we have just seen together to send a BIP47 payment:

- Alice selects the first private wrench derived from her personal payment code.

- She calculates a secret point on the elliptical curve with ECDH from the first unused child public key derived from the Bob’s payment code.

- She uses this secret point to calculate a secret shared secret with SHA256.

- She uses this shared secret to calculate a new secret point on the elliptical curve.

- She adds this new secret point with Bob’s public key.

- She obtains a new ephemeral public key for which only Bob has the associated private key.

- Alice can send a classic transaction to Bob with the ephemeral derived reception address.

If she wishes to make a second payment, she will reproduce the above -mentioned steps that she will select the second public key derived from the Bob payment code. That is to say the next unused key. It will then have a second reception address belonging to Bob “K1”.

It can thus continue immediately and derive up to 2^32 virgin addresses belonging to Bob.

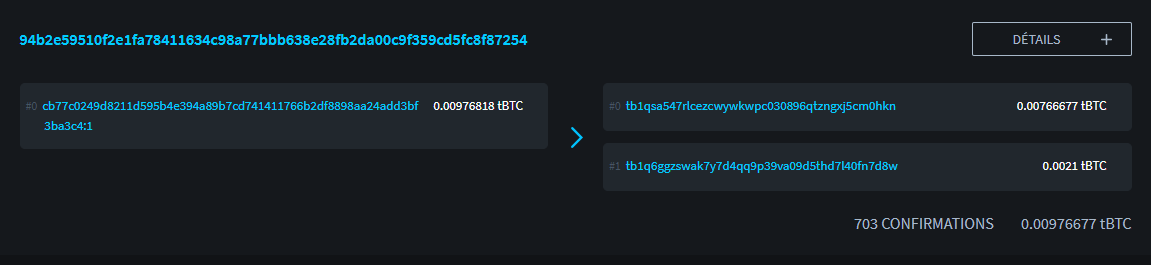

From an external point of view, by observing the Bitcoin blockchain, it is in theory impossible to differentiate a BIP47 payment from a conventional payment. Here is an example of a BIP47 payment transaction on the testnet:

https://blockstream.info/testnet/tx/94b2e59510f2e1fa78411634c98a77bbb638e28fb2da00c9f359cd5fc8f87254

TXID:

94b2e59510f2e1fa78411634c98a77bbb638e28fb2da00c9f359cd5fc8f87254

It looks like a conventional transaction with an input consumed, an output of payment of 210,000 SATS and a change:

Credit: https://blockstream.info/

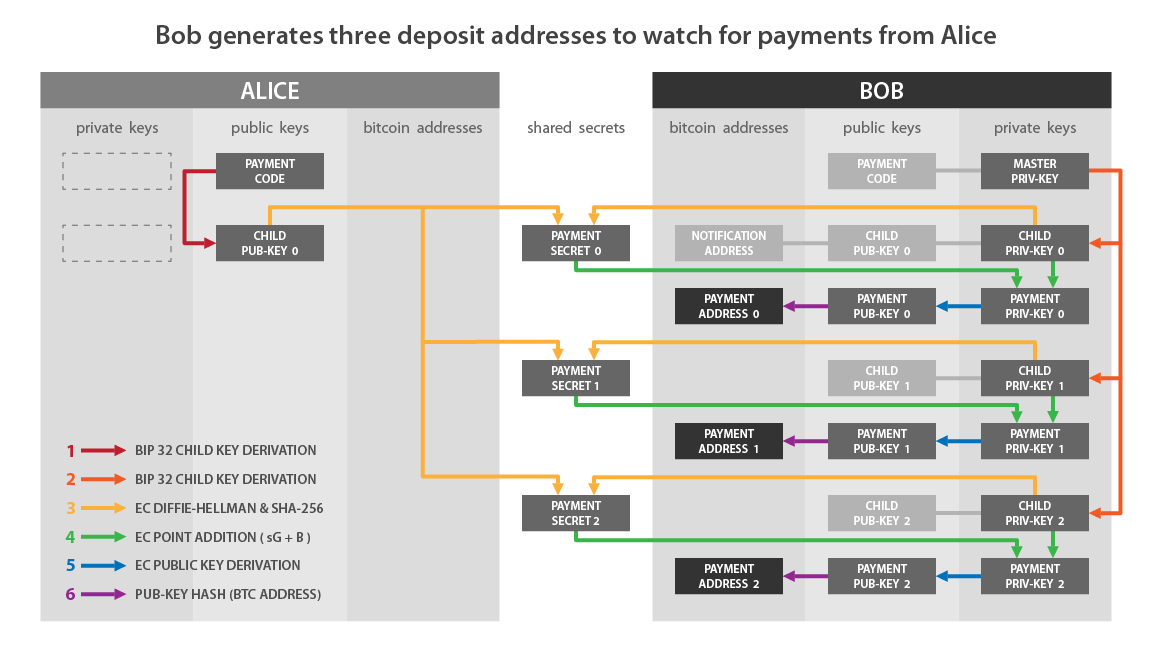

Reception of BIP47 payment and private key derivation #

Alice has just made her first payment to a virgin address BIP47 belonging to Bob. Now let’s see together how Bob receives this payment. We will also see why Alice does not have access to the private key to the address she has just generated, and how Bob finds this key to spend the bitcoins he has just received.

As soon as Bob receives the notification transaction from Alice, he derives the BIP47 “K0” public key even before his correspondent has sent payment. He therefore observes any payment to the associated address. In reality, he will even immediately derive several addresses he will observe (K0, K1, K2, K3 …). Here is how he derives this “K0” public key:

- Bob selects the first child private key derived from his payment code. This private key is named “b”. It is associated with the public key “B” with which Alice had made her calculations in the previous step:

b

- Bob selects Alice’s first public key derived from her payment code. This key is named “A”. It is associated with the private key “a” with which Alice had made her calculations, and of which only Alice is aware. Bob can carry out this process since he is aware of Alice’s payment code which was transmitted to him with the notification transaction.

A = a·G

- Bob calculates the secret point “S”, by adding and doubling points on the elliptic curve, by applying his private key “b” to Alice’s public key “A”. We find here the use of ECDH which guarantees us that this point “S” will be the same for Bob and for Alice.

S = b·A

- In the same way as Alice did, Bob isolates the abscissa of this point “S”. We named this value “Sx”. It passes this value into the SHA256 function to find the shared secret “s” (lowercase).

s = SHA256(Sx)

- Still in the same way as Alice, Bob calculates the point “s·G” on the elliptic curve. Then, he adds this secret point with his public key “B”. It then obtains a new point on the elliptic curve which it interprets as a public key “K0”:

K0 = B + s·G

Once Bob has this “K0” public key, he can derive the associated private key so he can spend his bitcoins. It is the only one who can generate this number.

- Bob adds his child private key “b” derived from his personal payment code. It’s the only one that can get the value of “b”. Then, it adds “b” with the shared secret “s” in order to obtain k0, the private key of K0:

k0 = b + s

Thanks to the group law of the elliptic curve, Bob obtains exactly the private key corresponding to the public key used by Alice. So we have:

K0 = k0·G

If we match this diagram with what I described to you previously:

- “Child Priv-Key 0” on the Bob side corresponds to: b.

- “Child Pub-Key 0” on the Alice side corresponds to: A.

- “Payment Secret 0” corresponds to: s.

- “Payment Pub-Key 0” corresponds to: K0.

- “Payment Priv-Key 0” corresponds to: k0.

I summarize the steps that we have just seen together to receive a BIP47 payment and calculate the corresponding private key:

- Bob selects the first child private key derived from his personal payment code.

- It calculates a secret point on the elliptic curve using ECDH from the first child public key derived from Alice’s chain code.

- It uses this secret point to calculate a shared secret with SHA256.

- It uses this shared secret to calculate a new secret point on the elliptic curve.

- He adds this new secret point with his personal public key.

- He obtains a new ephemeral public key, the one to which Alice will send her first payment.

- Bob calculates the private key associated with this ephemeral public key by adding his child private key derived from his payment code and the shared secret.

Since Alice cannot obtain “b”, Bob’s private key, she is unable to determine k0, the private key associated with Bob’s BIP47 receive address.

Schematically, we can represent the calculation of the shared secret “S” like this:

Once the shared secret is found with ECDH, Alice and Bob calculate the BIP47 payment public key “K0”, and Bob also calculates the associated private key “k0”:

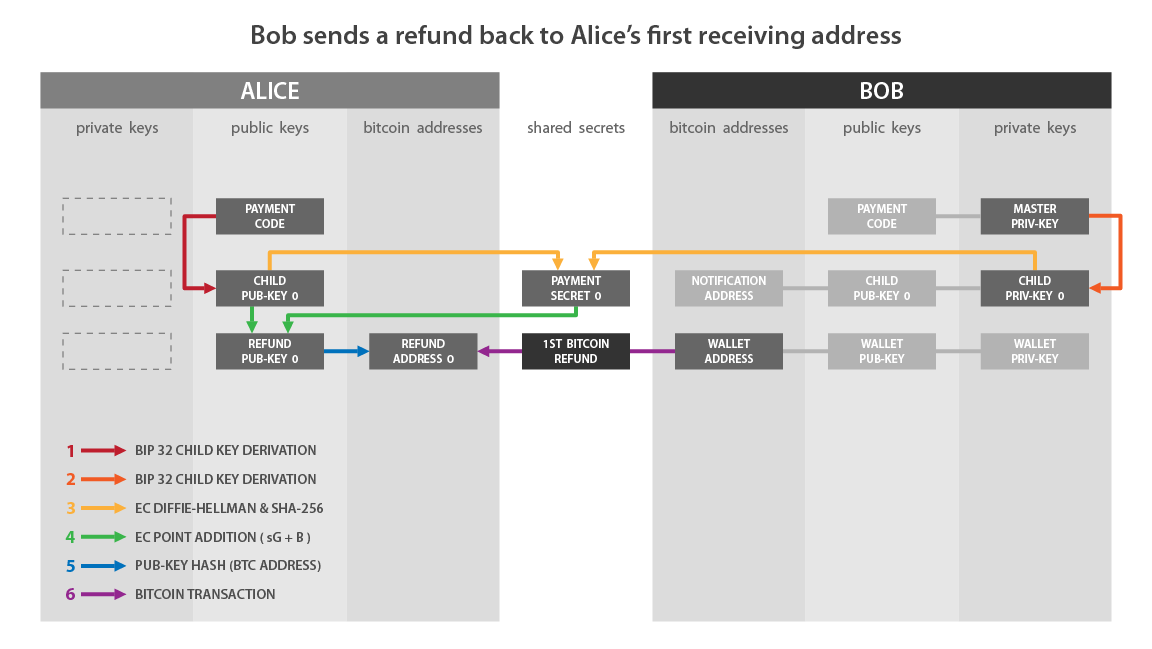

Refund of payment BIP47 #

Since Bob knows Alice’s reusable payment code, he already has all the information needed to send her a refund. He won’t need to contact Alice again to ask her for any information. He will simply have to notify her with a notification transaction, in particular so that she can recover her BIP47 addresses with her seed, then he can also send her up to 2^32 payments.

Bob can then repay Alice in the same way she sent payments to him. The roles are reversed:

You now know all the workings of this magnificent solution that the BIP47 represents.

Derivative Uses of PayNym #

The implementation of this BIP47 on Samourai Wallet gave PayNym, identifiers calculated from user payment codes. Today, their usefulness goes well beyond the use of the BIP47.

The Samourai teams are gradually developing an entire ecosystem of tools and services based on the user’s PayNym. Among these, there are obviously all the spending tools allowing to optimize the privacy of the user by adding entropy to a transaction, and therefore by adding plausible deniability.

The joint use of Soroban, the encrypted communication network based on Tor, and PayNym has made it possible to greatly optimize the user experience during the construction of collaborative transactions, while maintaining a good level of security. Thus, Stowaway (PayJoin) and StonewallX2 transactions can easily be carried out without manually carrying out the numerous exchanges of unsigned transactions necessary for setting up a collaborative transaction of this type.

Contrary to the use of the BIP47, since these collaborative transactions do not require a notification transaction to be carried out, it suffices to link the PayNyms to use these tools. There is no need to connect them.

In addition to these collaborative transactions, we have recently observed that the Samourai teams are working on an authentication protocol linked to PayNym: Auth47. This tool is already implemented and it allows, for example, to authenticate using a PayNym on a website that accepts this method. In the future, I think that beyond this possibility of authentication on the web, Auth47 will be part of a more global project around the BIP47/PayNym/Samourai ecosystem. Perhaps this protocol will be used to further optimize the user experience of the Samourai Wallet, especially in the use of spending tools. It is to be continued…

My personal opinion on the BIP47 #

Obviously, the main drawback of the BIP47 is the notification transaction. It leads the user to have to pay fees for mining it, which can be annoying for some. On the other hand, the argument of the “spam” of the Bitcoin blockchain is absolutely inadmissible. Anyone who pays the fees for their transaction must be able to put it on the ledger, regardless of their purpose. To say otherwise is to position oneself in favor of censorship.

It is possible that in the future, other less costly solutions will be found in order to be able to communicate the sender’s payment code to the recipient, and so that the latter can store it securely. But, for now, the notification transaction remains the solution with the least compromise.

This disadvantage remains negligible when all the benefits of BIP47 are observed. Among all the existing proposals to solve this address reuse problem, it appears to me to be the best solution.

As explained above, the majority of address reuse comes from exchanges. BIP47 is the only reasonable solution that actually solves this problem at the source. Any proposal to reduce the number of address reuses should address this aspect, and tailor the solution to the main source of the problem.

In terms of use, although its workings are quite complex, the BIP47 payment procedure is childish. Reusable payment codes can therefore be adopted easily, even by novice users.

In terms of confidentiality, the BIP47 is very interesting. As I explained in the notification transaction part, the payment code does not reveal any information about derived ephemeral addresses. It therefore makes it possible to break the flow of information between the Bitcoin transaction and the recipient’s identifier, unlike the traditional use of a receiving address.

And above all, the PayNym implementation of the BIP47 works! It has been available on Samourai Wallet since 2016, and on Sparrow Wallet since the start of the year. It is not a scientific project, but a solution tested yesterday, and completely functional today.

Hopefully, in the future, these reusable payment codes will be adopted by ecosystem players, implemented in wallet software, and used by bitcoiners.

Any truly positive solution for user privacy must be debated, pushed and defended, so that Bitcoin does not become CA’s playground, and government’s surveillance tool.

He thought of how he had been persecuted and insulted everywhere, and now he heard them all saying that he was the most beautiful of all these beautiful birds! And the very elder bent its branches towards him, and the sun shed such a warm and beneficent light! Then his feathers swelled, his slender neck lifted, and he cried with all his heart:

“How could I have dreamed of so much happiness, while I was but an ugly duckling.”

External resources and thanks #

- Thanks to LaurentMT and Théo Pantamis for the many concepts they explained to me, which I’ve used in this article. I hope I have transcribed them accurately.

- Thanks to Fanis Michalakis for proofreading this text and providing expert advice.

- https://bitcoiner.guide/paynym/

- https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0047.mediawiki

- Wikipedia: Diffie–Hellman key exchange

- Wikipedia: Elliptic-curve Diffie–Hellman

- https://security.stackexchange.com/questions/46802/what-is-the-difference-between-dhe-and-ecdh

- https://commandlinefanatic.com/cgi-bin/showarticle.cgi?article=art060

- https://ee.stanford.edu/~hellman/publications/24.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317339928_A_study_on_diffie-hellman_key_exchange_protocols